Even as Thimlich Ohinga’s dry stone walls crumble, the local community continues to be excluded from the management and care of the Kenyan UNESCO World Heritage site.

This according to Doreen Nyamweya who shares her second “Good Tourism” Insight. (You too can share your perspective.)

Thimlich Ohinga: Bitter irony

Last month, July 2025, I spent time in Migori County, Kenya, on a field visit for my MSc thesis on responsible tourism awareness levels among host communities in heritage destinations. While the aim of my visit was to collect data, I made a few observations that have shaped my broader perspective on heritage management.

I visited Thimlich Ohinga, a World Heritage Site in Migori, Kenya. During my time there, more questions than answers emerged on the impact of tourism on the local community.

Mainly, I was disturbed by the level of local exclusion from tourism activities around the Thimlich Ohinga. The centralisation of decision making on development, management, and heritage interpretation has sidelined the very people that have protected the local heritage for years. As a result, public appreciation of this important heritage site has weakened.

The bitter irony is that despite the World Heritage Convention’s 1972 legal framework prioritising cultural property preservation and nature conservation, policy for Thimlich Ohinga fails to set out clear guidelines and provisions for co-management agreements, local employment quotas, capacity-building programs, and benefit-sharing schemes.

Contents ^

What is Thimlich Ohinga?

Situated northwest of the town of Migori, in the Lake Victoria region, this dry stone walled settlement was probably built in the 16th century. The Ohinga (settlement) seems to have served as a fort for communities and livestock, but also defined social entities and relationships linked to lineage.

Thimlich Ohinga is the largest and best preserved of these traditional enclosures. It is an exceptional example of the tradition of massive dry stone walled enclosures, typical of the first pastoral communities in the Lake Victoria Basin, which persisted from the 16th to the mid-20th century.

Source: UNESCO (description available under license CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0).

Contents ^

Exclusion of locals threatens the cultural heritage of Thimlich Ohinga

In 2018, the UNESCO World Heritage designation for Thimlich Ohinga promised a tourism-led economic transformation for a region eager for development. But much like the promised benefits of tourism, improvements in accessibility, infrastructure, and amenities to facilitate tourism and other economic development are yet to materialise for the host community due to chronic underfunding.

Seven years on from World Heritage designation, an hour-long motorcycle ride is still the easiest and fastest way to access the Thimlich Ohinga heritage site. The road is rocky, bumpy, and some sections are barely passable during the rainy season.

So now locals’ interest in tourism development, and, more worryingly, their deep connection to their heritage and sense of collective responsibility for its protection, is weakening under the imposition of exclusionary heritage management practices.

The big problem is that Thimlich Ohinga heritage management staff are predominantly from outside the host community. Furthermore, businesses with no local ties, and tour operators based in distant cities, are reaping the bulk of whatever profits are available in an already frail market as small local vendors and community-owned guest houses struggle to compete against them.

Don’t miss other “Good Tourism” content about Africa

Contents ^

Exclusionary management is not necessarily a Kenya problem

Unlike Thimlich Ohinga, the “sacred” Mijikenda Kaya Forests, another Kenyan World Heritage site, successfully exhibits community inclusion and promotes community-led tourism initiatives through the involvement of village elders in decision-making processes.

Of course I realise that many heritage sites across Kenya may project success while struggling with the hidden impacts of tourism on host communities. These hidden impacts may go beyond economic exclusion to include cultural commodification, erosion of tradition, displacement, social disintegration, and environmental degradation that directly impacts community wellbeing. And many of these problems may be inevitable with or without local participation in decision making.

Regardless, at least locals have a say in their success … and in their failure.

Contents ^

Critical vulnerabilities are emerging at Thimlich Ohinga

How can something so near be so out of reach? My motorbike rider, though a resident of the community, admitted to not having been to the Thimlich Ohinga heritage site. He perceives it as a luxury to have to pay for access.

When partaking in a guided tour of the Thimlich Ohinga heritage site, my guide expressed concerns about how the low tourism activity in the area was failing to incentivise the community to protect it. The community was questioning why they should protect something that offers them no tangible benefit. Indeed growing resentment has made the heritage site vulnerable to neglect, exploitation, vandalism, and theft than ever before.

Another vulnerability is the chronic underfunding. Underfunding prevents heritage management from acquiring essential resources for maintenance, conservation work, and robust documentation. This has created a reactive approach to preservation rather than a proactive approach.

Damage is only addressed after it has occurred rather than prevented. In some instances, it is never addressed. For example, a collapsed section of wall has been left unrepaired despite presenting a potential hazard to visitors.

This sort of neglect extends to the fragmented legislative frameworks, creaking bureaucracy, and lack of distinct lines of responsibility between the destination management organisation, government bodies, and heritage organisations that compromise the conservation effort.

Nobody from outside the community who has assumed responsibility for Thimlich Ohinga appears to be prepared to fix the mess. Perhaps locals have the answers.

Another vulnerability is Thimlich Ohinga’s failure to embrace technology that might make it easier to make informed decisions about conservation priorities. Despite being in a digital age in 2025, many World Heritage Sites lack up-to-date data and the appropriate digitisation of asset inventories. Thimlich Ohinga is no exception. The heritage site processes access fee payments and visitor check-ins manually due to poor network connectivity.

Contents ^

We must avoid tears of division

For decades, communities have been the primary custodians of local cultural heritage. Indigenous knowledge of the land and folklore are an inherited responsibility passed down from generation to generation. It’s highly valuable; especially in the context of those people in that place.

However, as external interest in this indigenous heritage grows, and formal management structures are established to ‘manage’ and ‘preserve’ it, host communities can be dispossessed of their collective responsibility; the social cohesion necessary for the collective protection of their heritage can be undermined; and local commitment to holding on to what is theirs can be eroded.

What was once a source of pride and sense of local identity can start to feel like a corporate brand owned by others. Consequently, even the place ceases to feel like an ancestral home. Rather, it becomes just another attraction for outsiders; a theme park. The social fabric tears, driving exclusionary heritage management practices even further away from host communities.

Read more by Doreen Nyamweya

Contents ^

What now for Thimlich Ohinga?

The truth is that a strong, empowered community is the most resilient defence against many of these heritage management challenges. In years to come, there will be heritage sites that have got management right, and there will be those that have failed past the point of no return.

To move forward in Thimlich Ohinga, it is evident that localised solutions are needed. Blanket solutions have proven ineffective. Site-specific strategies must be developed together with the community if sustainable heritage management is to be realised.

First off, the host community at Thimlich Ohinga must be allowed to form appropriate community associations and/or cooperatives to provide some structure to their negotiations with external stakeholders. Cooperatives can help manage local services, prevent local exploitation, while promoting financial sustainability.

Beyond this, strong local representation on heritage management boards is fundamental. Local representatives can challenge outside “experts” by bringing insightful, on-the-ground context that will help bridge gaps between intention and consequence, inform pragmatic decision making, and improve accountability for local populations. Moreover, it will ensure interactions are more than tokenistic; that there is a genuine shared governance that accounts for local needs and interests.

And once that is achieved, host communities could then seek legal counsel to gain clarity on heritage ownership rights and appropriate governance structures. It will empower the host communities to negotiate for a ring-fenced level of involvement, investment, and fair share of any benefits of tourism and other economic development that taps the heritage value of the site.

Ultimately, UNESCO World Heritage sites like Kenya’s Thimlich Ohinga are a powerful reminder that the true resilience of cultural heritage lies not only in its physical preservation but also in the enduring inclusion of those who live with it: the host community.

Contents ^

What do you think?

Share your own thoughts about heritage management practices in Kenya or anywhere else in a comment below. (SIGN IN or REGISTER first. After signing in you will need to refresh this page to see the comments section.)

Or write a “GT” Insight or “GT” Insight Bite of your own. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion and perspective about travel & tourism, because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

“GT” doesn’t judge. “GT” publishes. “GT” is where free thought travels.

If you think the tourism media landscape is better with “GT” in it, then please …

About the author

Doreen Nyamweya, Tourism Officer in Nyamira County, Kenya, is a sustainable tourism specialist and a student and advocate of responsible tourism management.

Ms Nyamweya’s areas of expertise include tourism research, destination management, sustainability assessment, product development, and responsible tourism marketing.

You can connect with Doreen on LinkedIn.

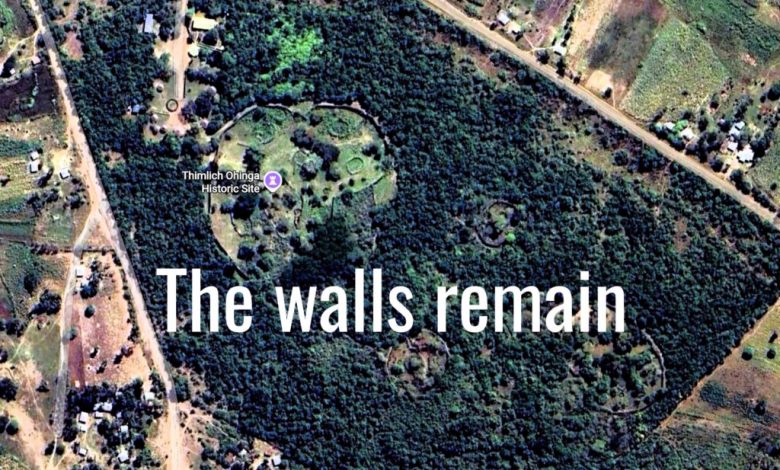

Featured image (top of post)

Google Map screen grab of Kenya’s Thimlich Ohinga, a UNESCO World Heritage site whose management lacks local community involvement according to Doreen Nyamweya.

Top ^